Original Articles

The clinical spectrum of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome: A single-center experience from South India

Padmamalini Mahendradas1*, Ankush Kawali2, Neha Bharti3, Dhawal Haria4, Poornachandra Gowda5, Naren Shetty4, Rohit Shetty5, Bhujang K Shetty6

Author Affiliations

1 Head of Department of Uveitis and Ocular Immunology, Narayana Nethralaya and Postgraduate Institute of Ophthalmology, 21/C, Chord road, Rajajinagar, Bangalore

2 Consultant, Department of Uveitis and Ocular Immunology, Narayana Nethralaya and Postgraduate Institute of Ophthalmology

3 Fellow Vitreo- Retina Services, Narayana Nethralaya and Postgraduate Institute of Ophthalmology

4 Post graduate, Narayana Nethralaya and Postgraduate Institute of Ophthalmology

5 Vice Chairman, Narayana Nethralaya and Postgraduate Institute of Ophthalmology

6 Chairman, Narayana Nethralaya and Postgraduate Institute of Ophthalmology

* Correspondence: Dr Padmamalini Mahendradas

IJRCI. 2013;1(S1):SO2

Received: 1 August 2013, Accepted: 18 December 2013, Published: 26 December 2013

© IJRCI

Abstract

Aim

To report the clinical features, investigations, management, and outcome in typical cases of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome (VKH) in a tertiary eye care center in South India.

Materials and methods

Retrospective interventional case series of VKH patients.

Results

Seventy-one eyes of 36 patients (age range 12-68 years) were included. Anatomical diagnoses were posterior uveitis (15 eyes) and pan uveitis (56 eyes). The classification of the cases with regard to VKH disease was as follows: six eyes were classified as complete, 41 eyes as incomplete, and 24 eyes as probable VKH disease. Commonest extraocular manifestation noted in 25 cases was headache. The more common ocular presentations were disc hyperemia (40 eyes) and exudative retinal detachment in the posterior pole (46 eyes) and in the retinal periphery (24 eyes). All patients were managed on systemic steroids. Systemic immunosuppressive therapy was given in 21 cases. Majority of the participants had good visual outcome.

Conclusion

Early recognition and aggressive treatment of VKH disease result in good visual outcome in typical VKH cases.

Introduction

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome (VKH) is an oculo-cutaneo-meningeal syndrome characterized by granulomatous panuveitis associated with neurological, auditory, and cutaneous manifestations. It is an autoimmune disorder directed against melanocytes in the uveal tract, meninges, inner ear, and skin. The disease is commonly seen in pigmented races. Asians, Native Americans, Hispanics, Asian Indians and those with Middle Eastern heritage are most frequently affected, but interestingly the disease is rare among Sub-Saharan Africans, indicating that the amount of skin pigmentation alone is not the sole etiologic factor in the pathogenesis of VKH syndrome.1 Identification of association with major histocompatibility complex class II antigens, strongly supports an underlying genetic predisposition in the pathogenesis of the disorder.

In Japan, VKH disease accounts for more than 8% of uveitis, 2.9% in the Middle East, 1.2% in Europe and 1% to 4% in the United States.2, 3 In a study done at one of the referral eye care centers in South India, the prevalence of VKH in uveitis cohorts was found to be 1.4% to 3.5%.4

Though ocular manifestations are common, VKH patients frequently land up in general physician’s clinic or they are referred to neurologist for their extra-ocular features like meningism and undergo unnecessary investigations and imaging, which may further delay the treatment. The disease has very good prognosis when managed in time by an ophthalmologist.

The aim of this study is to analyze demographics, clinical characteristics, treatment response, and complications in VKH patients referred to a tertiary eye care center in South India.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective, non-randomized, non-comparative interventional case series. Patients diagnosed as typical VKH disease presenting to the department of uveitis and ocular immunology between January 2005 and December 2012 in a tertiary eye care center in Bangalore, India were included in the study.

Institutional ethical committee approval was obtained for the retrospective chart review for this study. The clinical records of 35 patients diagnosed with VKH were reviewed for patient demographics, clinical signs, investigations, treatment received, complications, and visual outcome. All patients underwent a complete ophthalmic examination, including measurement of best corrected visual acuity (VA), slit-lamp examination, applanation tonometry, dilated fundus examination with scleral indentation, colour fundus photography, and ocular ultrasonography (if the view of the fundus was not clear). External examination evaluated the presence of poliosis and vitiligo.

The diagnosis of VKH disease was made according to the clinical presentations and it was confirmed by fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) in all cases. Additional investigations such as B-scan ultrasonography, spectral domain optical coherence tomography (Spectralis, Hiedelberg engineering) and indocyanine green angiography (ICG) was done in selected cases. A history of trauma was ruled out in all cases. Investigations were done to rule out tuberculosis (Mantoux skin hypersensitivity test, PA view of chest X-ray), syphilis (Treponema pallidum hemaglutination) and sarcoidosis (serum angiotensin converting enzyme).

We used revised diagnostic criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease by Read et al. for classifying the study participants into complete, incomplete, and probable VKH.5 All patients with associated diseases such as tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, syphilis or trauma were excluded. All the patients were treated with systemic corticosteroid therapy. Topical corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy were used in selected cases. Statistical analysis was done using the SPSS version 12 software.

Results

Thirty-five patients were included in the study. Age group of the subjects ranged between 12-68 years (mean 34.1 years). Eleven patients were male and 24 patients were female. Thirty-four patients had bilateral presentation and 1 patient had unilateral VKH. The clinical type of VKH disease was classified as complete in 3 patients, incomplete in 20 patients, and probable in 12 patients.

Clinical presentation was posterior uveitis in 15 eyes and panuveitis in 55 eyes. Thirty eyes (42.8%) had acute VKH disease, 28 eyes (40%) had chronic presentation, and 12 eyes (17.1%) had recurrent uveitis. (Table 1)

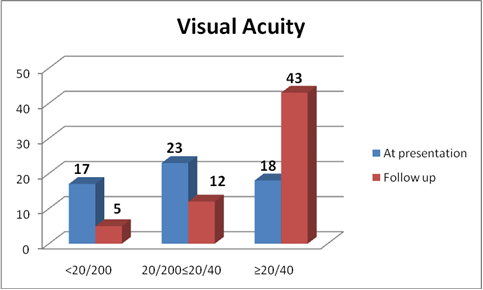

Meningism and headache were the commonest acute presentations followed by poliosis and vitiligo in chronic cases. Sensorineural hearing loss was present in 2 cases (Table 2). Eighteen eyes presented with best corrected visual acuity of 20/200 or worse at presentation (Fig 5). The ocular findings of slit-lamp examination were circumciliary congestion in 38 eyes (54.2%), keratic precipitates in 34 eyes (49.2%) and iris nodules in 12 eyes (17.1%) with the presence of anterior chamber flare and cells (Table 3). Fundus examination revealed vitritis in 70 eyes (100%), optic disc involvement in 40 eyes (57.1%), exudative retinal detachment in 45 eyes (64.2%), choroidal detachment in 5 eyes (7.1%), sunset glow fundus in 39 eyes (55.7%), and Dalen-Fuchs nodules in 20 eyes (28.5%) (Table 3). FFA was done in all patients, which revealed multiple hyperfluorescent dots at the level of retinal pigment epithelium in 30 eyes, optic disc leakage in 55 eyes, and late accumulation of fluorescein in the subretinal space in 31 eyes. The ICG showed early hypofluorescent spots, diffuse choroidal hyperfluorescence, and choroidal perivascular leakage in 16 cases. Follow-up ICG conducted after 6-8 weeks revealed multiple hypofluorescent lesions, even when the fundoscopic examination and FFA were unremarkable in 13 cases. Low- to medium- reflective diffuse thickening of the choroid was demonstrated by 20 MHz ultrasonography and was most marked in the juxtapapillary region. This was associated with retinal detachments in 45 eyes and choroidal detachments in five acute cases. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) findings in VKH in active state were multi-lobular serous retinal detachments, intra-retinal edema, subretinal septae, and dot reflex in subretinal space. Dalen-Fuchs nodules and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and choriocapillary hypertrophy were noted in chronic VKH cases.

Treatment duration ranged from 6 to 36 months (mean 18 months). Patients with anterior segment inflammation were treated with topical corticosteroids and cycloplegic agents, in addition to systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Two patients who could not tolerate the systemic immunosuppressive therapy due to transient increase in liver enzymes were treated with bilateral periocular posterior subtenon’s triamcinolone acetonide injection and subsequently with systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Intravenous methyl prednisolone 1gm once daily for three days was given to 17 patients (48.5%) who had serous retinal detachment. Oral prednisolone acetate was given to all the patients (Table 4). The median duration of oral prednisolone was 7 months (range 6-12 months). Two patients who developed diabetes mellitus during the course of the disease switched over to deflozacort along with azathioprine.

Oral immunosuppressives were used for a median duration of 14 months (range 6-30 months) in 22 patients (62.81%). Drugs such as methotrexate (14 patients), azathioprine (11 patients), mycophenolate mofetil (2 patients) and cyclosporine (1 patient) were used (Table 4). Six patients received two immunosuppressive drugs and triple immunosuppressive therapy comprising of mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporine along with tapering dose of oral steroids by one patient. Once the ocular inflammation and retinal detachments had resolved, the fundus changes showed near normal fundus in 5 patients and pigmentary changes with sunset glow fundus in 15 patients of acute uveitis and all patients of chronic and recurrent uveitis. Recurrences were seen in 12 eyes (panuveitis in 8 eyes and posterior uveitis in 4 eyes).

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics of VKH patients

|

Demographic variables |

No. (%) |

|

Mean Age (yrs) |

34.1 (11- 68) |

|

Gender Male Female |

11(31.4%) 24 (68.5%) |

|

Laterality Bilateral |

35 (100%) |

|

Anatomical classification Panuveitis Posterior |

55 eyes (78.9%) 15 eyes (21.1%) |

|

Clinical types Probable Incomplete Complete |

24 eyes / 12 patients (34.2%) 40 eyes / 20 patients (57.1%) 6 eyes / 3 patients (8.5) |

|

Course Acute Chronic Recurrent |

30 eyes (42.8%) 28 eyes (40%) 12 eyes (17.1%) |

Table 2: Incidence of diverse systemic manifestations

|

Systemic manifestations |

No. (%) |

|

Meningismus

Headache

Poliosis

Vitiligo

Hearing loss

Tinnitus |

20 (57.1)

20 (57.1)

8 (11.4)

12 (34.2)

2 (5.7)

14 (40) |

Table 3: Clinical findings on anterior and posterior segment manifestations

|

Anterior segment manifestations |

No. (%) |

|

Circumciliary congestion |

38 eyes (54.2) |

|

Keratic precipitates (KP) Fine KPs Mutton fat KPs |

34 eyes (49.2) 24 eyes (34.2) 10 eyes (14.2) |

|

Iris nodules |

12 eyes (17.1) |

|

Flare 1+ 2+ 3+ |

45 eyes (64.2) 23 eyes (32.8) 19 eyes (27.1) 3 eyes (4.2 ) |

|

Cells 1+ 2+ 3+ |

52 eyes (74.2) 24 eyes (34.2) 25 eyes (35.7) 3 eyes (4.2) |

|

Posterior segment manifestations |

No. (%) |

|

Vitritis 1+ 2+ 3+ |

70 eyes (100) 52 eyes (74.2) 16 eyes (22.8) 2 eyes (2.8) |

|

Disc hyperemia |

40 eyes (57.1) |

|

Disc edema |

40 eyes (57.1) |

|

Retinal detachment Posterior pole Periphery |

45 eyes (64.2) 45 eyes 24 eyes |

|

Sunset glow fundus |

39 eyes (55.7) |

|

Dalen-Fuchs nodules |

20 eyes (28.5) |

|

Choroidal detachment |

5 eyes (7.1) |

Table 4: Medical management of VKH syndrome

|

Drugs used |

No. (%) |

|

Topical corticosteroids |

61 eyes (87.1) |

|

Oral steroids |

35 patients (100) |

|

Periocular steroids |

2 patients (5.7) |

|

Intravenous methyl prednisolone |

17 patients (48.5) |

|

Immunosuppressive |

22 patients (62.8) |

|

Methotrexate |

14 patients (40) |

|

Azathioprine |

11 patients (31.4) |

|

Cyclosporine |

1 patient (2.8) |

|

Mycophenolate mofetil |

2 patients (5.7) |

|

Patients on more than one immunosuppressives |

6/22 patients (17.1) |

|

Patients on more than two immunosuppressives |

1/22 patient (2.8) |

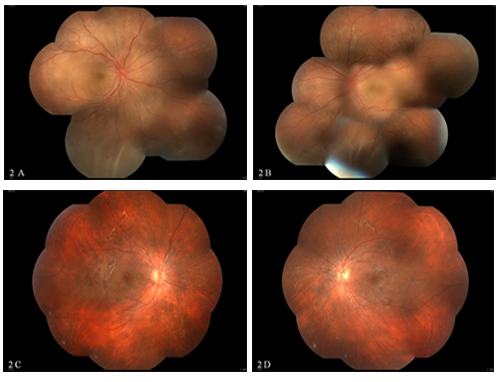

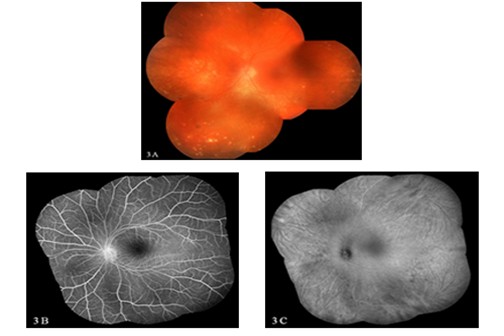

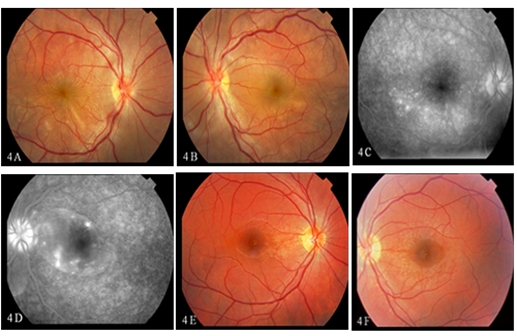

Figures 1- 4 indicate illustrative clinical findings observed in VKH patients

Figures 1A - 1C : Extraocular manifestations in chronic VKH syndrome

Figures 2A, 2B: Montage colour fundus photograph of the right eye (Figure 2A) and left eye (Figure 2B) showing the hyperemic disc, multiple serous retinal detachments in the posterior pole with inferior exudative retinal detachments. Patient was treated with IVMP followed by oral steroids and systemic methotrexate therapy. The patient further presented with recurrence of inflammation after stopping the systemic immunosuppressive therapy on her own. Subsequently, she was treated with systemic steroids and methotrexate therapy. Follow-up picture 2C and 2D reveals sunset glow fundus with subretinal fibrosis.

Figure 3: Chronic VKH-fundus photograph showing sunset glow fundus with Dalen-Fuchs nodules in the left eye. FFA & ICG: Montage image showing normal fluorescein angiogram with hypofluorescent dark spots in the indocyanine angiography suggestive of active lesions in the choroid.

Figure 4: A 21-year-old male diagnosed to have bilateral exudative retinal detachment (Figure 4A, 4B) with multiple pinpoint hyperfluorescence with pooling of the dye (Figure 4C, 4D) treated with triple immunosuppressive therapy, showing complete resolution of the inflammation in both eyes (Figure 4E, 4F).

Visual outcome

In our series of patients, a better than or equal to 20/40 VA was maintained in 54 eyes, while 5 eyes had poor visual outcome due to cataract formation (Fig 5).

Complications

Complicated cataract, seen in 20 eyes, was the commonest ocular complication. Increased intraocular pressure in 8 eyes and hypotony and subretinal fibrosis in 2 eyes (Table 6) were also noted. Extraocular manifestations were seen in chronic and recurrent cases. Two patient developed urinary tract infection due to E. Coli infection and one patient developed pneumonia. All the three patients were managed with appropriate systemic antibiotic therapy. Transient increase in liver enzymes was observed in 2 patients.

Fig 5: Visual acuity at presentation and at final follow-up

Discussion

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (VKH), a multisystem autoimmune disorder targeting predominantly melanocytes, affects organs such as eye, skin, inner ear and meninges. In the eye, the disease affects the uveal tract, manifesting as granulomatous panuveitis. Acute presentation is characterized by the presence of exudative retinal detachment with preservation of the choriocapillaris. In the chronic stage, the disease is characterized by the presence of Dalen-Fuchs nodules and focal chorioretinal atrophy with loss of retinal pigment epithelium.6 In chronic stage, patients develop extraocular manifestations. The findings from our study as well as from the earlier reports show that women are more likely to develop VKH disease than men, whereas Soon-Phaik Chee et al. have reported equal distribution in both sexes.7-10, 11 The observations in elderly patients were similar to the study by Kiyomoto et al.12

The present study findings are similar to that of Ilknur Tugal-Tutkun et al. With regard to clinical types of the disease, incomplete VKH (57.7%) was identified as the commonest followed by probable (33.8%) and complete forms (8.4%) as published by Ilknur Tugal-Tutkun et al.13

Extra-ocular manifestations were seen in chronic cases and the results were similar to hispanic population.14 Whereas these manifestations are more common in studies involving Japanese patients.12 The early and aggressive use of corticosteroids in acute VKH disease prevented the appearance of the complete spectrum of the disease in the current study, as shown by Rajendram et al.15 Systemic steroid therapy was given for longer periods of time along with immunosuppressive therapy.

The diagnosis of VKH disease is based on history and clinical findings with supportive evidence from ancillary tests, including fundus fluorescein angiography, which showed classical presentation such as multiple pin-point hyperfluorescence in the early phase at the level of the RPE, with classical pooling of the dye in the late phase in all acute presentations. ICG angiography showed more extensive areas of involvement characterized by staining and leakage of the larger choroidal vessels with multiple hypofluorescent dark spots.16, 17

In chronic cases, even in the absence of inflammatory activity on fundus examination and fluorescein angiography, ICGA showed the presence of multiple hypofluorescent dots suggestive of active inflammation in the choroid, which helped us to continue the systemic immunosuppressive therapy. OCT was used when the media was clear to document the changes and B scan was used in all acute cases and also in cases of hazy media, where we could not visualize the fundus to monitor the response to treatment.

All our patients were treated with systemic steroid therapy. Periocular steroid injections were given in 2 eyes when the systemic immunsupppressive therapy was contraindicated due to systemic infection. Systemic immunosuppressive therapy was given to patients who needed prolonged high-dose corticosteroids and also in chronic recurrent disease. Systemic immunosuppressive therapy was administered to 61.1% of the patients. Double immunosuppressive therapy was given in 27.3% cases. Triple immunosuppressive therapy (4.5%) with mycophoelate mofetil, cyclosporine and systemic steroids were given to one patient and it resulted in good control of inflammation with good visual recovery. Further prospective evaluation of the role of immunomodulatory agents in the treatment of VKH disease is recommended due to small cohort size and retrospective nature of the present study.

CSF analysis was not done in majority of the cases and hence the probability of CNS being not involved is primarily due to the absence of clinical signs and symptoms. Other limitations of the present study were non-inclusion of atypical presentations and small study cohort size. We found that the most frequent ocular complication of VKH disease was cataract (20 eyes, 28.1%), which is similar to other earlier studies.5, 18, 19 Further multicentric prospective studies to explore role of immunomodulatory agents in the treatment of VKH disease are recommended.

In summary, the clinical features of VKH in South India are similar to the earlier reports, except for the increased presentations of posterior segment inflammations than the anterior segment reactions during the recurrences.8 Extra ocular manifestations were not noticed in acute cases with aggressive management with systemic steroids and immunosuppressive therapy. Chronic and recurrent cases had extraocular manifestations at the time of presentation in majority of the cases. Early and aggressive therapy resulted in good visual outcome in majority of our patients.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of the treating physicians (Dr. Keerthy Shetty and Dr. Shylaja Shyamsundar) and the immunologists (Dr. Chandrasekara, Dr. Dharmanand, Dr. Mahendranath, Dr. Ramesh Jois and Dr. Sathish Kalange) for helping us with the systemic management.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

1. Fang W, Yang P. Vogt-koyanagi-harada syndrome. Current Eye Research. 2008;33(7):517-517.

2. Wakabayashi T, Morimura Y, Miyamoto Y, Okada AA. Changing patterns of intraocular inflammatory disease in Japan.OculImmunolInflamm. 2003;11:277-286.

3. Nashtaei EM, Soheilian M, Herbort CP, Yaseri M. Patterns of Uveitis in the Middle East and Europe. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2011 Oct;6(4):233-40.

4. Martin TD, Rathinam SR, Cunningham ET Jr. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and causes of vision loss in children with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease in South India. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa). 2010 Aug;30(7):1113-21.

5. Read RW, Holland GN, Rao NA, Tabbara KF, Ohno S, Arellanes-Garcia L, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: report of an international committee on nomenclature. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001 May;131(5):647-52.

6. Rao NA. Pathology of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Int Ophthalmol. 2007 Jun;27(2-3):81-5.

7. Khairallah M, Zaouali S, Messaoud R, Chaabane S, Attia S, Ben Yahia S, et al. The spectrum of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease in Tunisia, North Africa. Int Ophthalmol. 2007 Jun;27(2-3):125-30.

8. Murthy SI, Moreker MR, Sangwan VS, Khanna RC, Tejwani S. The spectrum of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease in South India. Int Ophthalmol. 2007 Jun;27(2-3):131-6.

9. Moorthy RS, Inomata H, Rao NA. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995 Jan-Feb;39(4):265-92.

10. P E Rubsamen JDG. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Clinical course, therapy, and long-term visual outcome. Archives of ophthalmology. 1991;109(5):682 Mahendradas P, Kawali A, Bharti N, Haria D, Gowda P, Shetty N, Shetty R, Shetty BK. The clinical spectrum of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome: A single-center experience from South India. IJRCI. 2013;1(S1):SO2.

11. Chee S-P, Jap A, Bacsal K. Spectrum of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease in Singapore. Int Ophthalmol. 2007 Jun;27(2-3):137-42.

12. Kiyomoto C, Imaizumi M, Kimoto K, Abe H, Nakano S, Nakatsuka K. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease in elderly Japanese patients. Int Ophthalmol. 2007 Jun;27(2-3):149-53.

13. Tugal-Tutkun I, Ozyazgan Y, Akova YA, Sullu Y, Akyol N, Soylu M, et al. The spectrum of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease in Turkey: VKH in Turkey. Int Ophthalmol. 2007 Jun;27(2-3):117-23.

14. Beniz J, Forster DJ, Lean JS, Smith RE, Rao NA. Variations in clinical features of the Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa). 1991;11(3):275-80.

15. RajendramR,Evans M,RaoNA.Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2005; 45:115-134.

16. Fardeau C, Tran THC, Gharbi B, Cassoux N, Bodaghi B, LeHoang P. Retinal fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography and optical coherence tomography in successive stages of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Int Ophthalmol. 2007 Jun;27(2-3):163-72.

17. Herbort CP, Mantovani A, Bouchenaki N. Indocyanine green angiography in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: angiographic signs and utility in patient follow-up. Int Ophthalmol. 2007 Jun;27(2-3):173-82.

18. Mondkar SV, Biswas J, Ganesh SK. Analysis of 87 cases with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2000 Jun;44(3):296-301.

19. Belfort Junior R, Nishi M, Hayashi S, Abreu MT, Petrilli AM, Plut RC. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada’s disease in Brazil. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1988;32(3):344-7.